From Italy to Belmont County: One Family’s Journey

- Cathryn Stanley

- Aug 12, 2023

- 18 min read

Immigration, Coal, and Belmont County in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

Written & Researched by Patti Marinelli

Introduction

During the early 1900s, the United States experienced a great wave of immigration, especially from Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe. Among the millions of immigrants from Italy during that time was Alberto (Albert) Marinelli. His ties to Ohio began when his father decided to leave their village in central Italy and seek work in the coal mines of Belmont County. The family of Alberto’s wife-to-be, Gilda Capitini, had undertaken that same voyage of hope from Italy to the Ohio Valley some years earlier.

In both cases, coal mining became a central part of their daily lives: Miners provided for their families; shift work helped shape their family’s daily routines; dangerous mining conditions often brought worry to miners and families alike.

Alberto and Gilda’s story shares common threads with the tales of the many immigrants who made a new life in Belmont County and helped form the unique character of the area.

Alberto: Early life in Italy and the impact of the Great War

Alberto Marinelli grew up in the mountainous, sparsely-settled region of Abruzzo, where he lived with his parents and two brothers. In the early 1900s, the Marinelli family -- like many of the residents of his small village of Barisciano -- managed to make a modest living by tending sheep and cultivating a vegetable garden. Their home at number 7 Vico Zolfo had two stories: The lower level served primarily as storage for equipment and a stable for livestock; the upper level was the family’s living quarters. Like their neighbors, the Marinelli family spoke a regional Italian dialect at home; the three boys attended a local school, where they learned to read and write standard Italian.

Beginning in 1914, the international conflict later known as the Great War (or World War I) embroiled most of Europe, Russia, and parts of the Middle East. A year later, that war reached Italy. Even the remotest parts of the nation were affected, as peasants and laborers were heavily conscripted to fight in the army. Alberto’s father, Giuseppe Antonio (Joseph Anthony), was one of those recruited to serve in the war.

After the end of the Great War, in 1918, Italy found itself in dire economic straits and faced growing political turmoil. Returning soldiers struggled to find work as unemployment rates reached high levels. Now discharged from the army, Giuseppe Antonio needed to find a way to provide for his family and keep them safe. He knew that other residents from his town and region had already immigrated to the United States; many had made their way to Belmont County, where the coal mines provided work even to those who didn’t speak English. So, in 1920, Giuseppe Antonio made plans to emigrate from Italy. His voyage by ship took him to New York; from there he made his way to Belmont County.

This image displays the passport pages, opened and flattened:

In this three-page view, the page on the left indicates that departure to the U.S. will take place between December 8, 1920, and June 8, 1921.

The center page has the visa number and indicates that the trip will be undertaken by ship.

The cover, on the far right, identifies the passport holder; the translation from Italian follows:

In the name of His Majesty Vittorio Emanuele III [Victor Emmanuel III]

By the grace of God and by the Will of the Nation

King of Italy

Passport Issued to: Marinelli Giuseppantonio

Son of: the deceased Giulio

And of: the deceased Strussione Palmira Born in: Barisciano Province of: Aquila On: January 22, 1879

Resident of: Barisciano Province of: Aquila

Marital status: Married

Profession: Farm laborer

Knows how to read: Yes

Knows how to write: Yes

Military service status: Discharged from active duty

Police headquarters: Aquila

In this three-part image, the passport page on the left has the photo of Giuseppe Antonio and his identifying characteristics.

The middle page is an insert from the Swiss Delegation in Rome, which expedited the visa. It indicates that the voyage would be to “America” and last “5 days”.

The right-hand page indicates the date of issue as October 20, 1920, and the destination as New York.

Here is the translation into English of the left-hand page, which is signed by the police commissioner of the province of Aquila. The two-lira stamp at the bottom left of the page is a revenue stamp, which was commonly required for official documents.

Height: 1.66 (meters) Forehead: High Eyes: Brown

Nose: regular Mouth: Regular Hair: Brown Beard: Clean-shaven

Mustache: Yes Coloring: Natural Build: Average

Distinguishing characteristics: (blank)

Alberto: Mining coal, saving money, and buying tickets

Coal mining began in Ohio even before it became a state. By the early 1900s, Belmont County had become an important producer of coal. Not only did the rich Pittsburgh coal seam #8 lie beneath the county’s lands but the Ohio River and the extensive railroad system in the area provided convenient ways to transport coal to other markets.

Like many immigrants to Belmont County, Giuseppe Antonio Marinelli –Alberto’s father-- found employment in the coal mines. The work in the area’s smaller mines was hard. Miners used picks, shovels, and some small explosives to mine the coal; and mules with carts to transport it to the surface. However, by boarding with cousins to save money, after seven years of coal mining Giuseppe Antonio was able to pay for the passage of his three sons to the United States.

He brought over his oldest, Raffaele (Ralph) in July of 1928. Alberto followed in December of that same year, and the youngest, Giovanni (John) arrived in May of 1930. Giuseppantonio’s wife refused to leave her home in Italy, to the sorrow of her children.

Giuseppe Antonio bought the tickets for Alberto in the United States and paid for them at the First National Bank in Bellaire. Here are some details from the receipt:

The voyage by ship would be in third class and depart from Naples, Italy.

The price of the voyage was $100.

The price of the rail trip from New York to Bellaire, Ohio, was $18.33.

There was a “head tax” of $8.00. (The head tax was a fairly new immigration requirement at that time.)

Assistant cashier R. N. Perkins, who worked as a sub-agent for the Society of Maritime Trade at the First National Bank in Bellaire, accepted a total payment of $126.33 (worth about $2000 in the year 2022).

Alberto: Preparing for the trip to America

In reaction to the great wave of immigration to the United States during the late 1800s

and the early 1900s, the federal government implemented a series of new requirements

that immigrants would need to follow. As Albert’s turn to emigrate from Italy drew near,

he began gathering all the necessary paperwork and applying for a passport.

In order to be eligible to immigrate to the United States, Albert had to obtain sworn

statements from local and provincial authorities that attested to his good health, his lack

of any criminal record, and his ability to read and write in Italian. To prove that he was

literate in Italian, Alberto carried with him a school certificate that attested to his having

passed all the written, oral, and practical exams for the second cycle of elementary

school. At the time in Italy, pupils were required to attend school only through the age of

12; Alberto’s formal education stopped at that point, as he needed to help with the

family farm.

In the early 1900s in Italy, pupils had to pass year-end evaluations to be promoted to the next grade. These evaluations were written, oral, and practical (that is, by demonstrating a skill) ; they were scored on a scale of one to ten. Translation of the school certificate, with the hand-written parts in boldface:

Province of Aquila Town of Barisciano

Elementary School for Boys (Males)

Certificate of Promotion

It is hereby declared that Marinelli Alberto Son of Giuseppe born In Barisciano on January 31, 1911 [sic] coming from a public school Was promoted to the 3rd class having earned the following scores:

Written evaluations:

Conduct (Deportment) eight Writing and dictation eight

Handwriting Seven

Composition Seven

Arithmetic Seven

The right-hand page of the passport features Alberto’s photograph, the required revenue stamps, and Alberto’s signature. This is followed by a sworn statement from an official of the province of Aquila attesting that this is indeed Alberto’s signature.

The left-hand page of Alberto’s passport has the following information, translated into English:

Information and characteristics of the holder Profession: Laborer

Son of: Giuseppantonio

And of: DelCotto Giovanna

Born in: Barisciano

On: December 15, 1910

Residing in: Barisciano Province of: Aquila

Height: 1.89 (meters)

Eyes: Brown

Hair: Brown

Beard: [crossed out] Mustache: [crossed out] Coloring: Natural Distinguishing marks: [left blank]

Alberto: Making his way to the ship

With his passport and ticket in hand, Alberto –who turned 18 during the trip-- began his

solo journey from Italy to the United States, and ultimately to Belmont County.

First, he had to make his way from his hometown of Barisciano in eastern Italy to the

southern port city of Naples, more than 150 miles away. Nothing is known about this

part of the trip.

Before boarding the ship in Naples, all passengers, including Alberto, had to undergo a

health inspection and “remediation”, a requirement of the authorities in the United

States.

In the image, the health inspection card is opened flat; the image on the left is the back of the card; the image on the right is the front of the card.

The left half of this image describes what food and lodging will be provided to transatlantic passengers: lunch, supper, and a bed on the night before departure; breakfast and lunch on the day of departure.

The right half of the image identifies the passenger; here is the translation in English.

Inspectorate of Emigration of Naples Health Services

Certificate of Arrival

And Health Card

Of the emigrant: Marinelli Alberto

Son of: Giuseppe Age: 18

From: Barisciano

Departing from: Naples

On the Ship: Augustus

Of the Shipping Firm: Navigazione Generale Italiana On: December 12, 1928

Destination: New York

Date of presentation: December 7, 1928

“Emigrants Should Keep This Document”

The inside of the Health Inspection Card has Alberto’s photograph and indicates what preventive measures were taken to assure the health of the passengers. There are various stamps by each category to indicate that the required inspections were completed. Here is a translation:

Inspectorate of Emigration of Naples

Health Remediation Station

Inspection and disinfection of baggage

Cleanliness of the head

Bath or shower

Disinfection of clothing

Vaccination or revaccination

Signs of illness or physical imperfections

“Important: Every emigrant should have a small carry-on with at least two changes of clean underwear, one of which he should put on after the remediation (decontamination).”

Alberto: Making the voyage to America, in December 1928

A few days after his health inspection, Alberto boarded the ocean liner Augustus, which

took him from Naples to New York City, a journey of about nine days.

At that time, the Augustus was the largest diesel-powered ship in the world. It could hold

302 first-class passengers, 338 second-class passengers, 166 tourist-class passengers,

372 third-class passengers in cabins – like Alberto--, and 938 “ordinary” third-class

passengers.

Here is the translation of the key information on the front of the ocean liner ticket:

Navigazione Generale Italiana [name of the ship liner]

Naples Office for Third-Class Passengers

Boarding Ticket for 1 passenger for Third Class

On the Ship under the Italian Flag: Augustus

That will depart from Naples on December 12, 1929

Duration of the trip: 9 days (including stops at ports of call)

Surname and name: Marinelli Alberto

Age: 18

Berth: 1

Rations: 1

Cabin Number: 12

Bed number: B

This ticket includes the right to 100 kilos of baggage, provided it is not greater in size than half of a cubic meter. There is a charge for excess baggage.

Naples, December 1, 1928

Note: Passengers who do not present themselves to the Office of Third Class Passengers on the night before departure can be refused boarding.

The paragraphs at the top of the ticket, designated “Article 37” and “Article 40”, summarize regulations regarding how passenger complaints will be handled. The extract from “Article 74” explains how reduced fares are calculated for children: up to 1 year of age, free; from 1 year to 5 years old, they must pay ¼ of the fare; from 5 to 10 years of 10, half price; from 10 up, full fare.

The two charts in the middle of the ticket provide details about what kinds and quantities of food will be served to the third-class passengers. By regulation, the table on the left applies to emigrants from southern Italy; the table on the right applies to emigrants from northern Italy. These two menus reflect the regional culinary preferences of the two major parts of Italy.

The first column in each chart lists the days of the week; the first row lists the two meals (lunch and supper), followed by a list of basic foods and how many grams will be provided for each, according to the day of the week.

Here are some examples: [for emigrants from southern Italy]

Every morning: Coffee and bread or coffee and biscotti

Monday – Lunch: pasta with canned tomatoes; stewed meat with potatoes

Monday – Supper: pasta in broth; boiled meat and pickled vegetables

Basic foods [vary by day of the week]

Fresh bread, good quality, 500 grams

Meat, 300 grams

Pasta, good quality, hard wheat, 250 grams

Cod, 100 grams

Tuna in olive oil, 80 grams

Lard, 15 grams

Beans, 100 grams

Lentils, 50 grams

….

Coffee, good quality, 15 grams

Sugar, 20 grams

Italian wine, half a liter

For emigrants from northern Italy, the foods for breakfast, as well as the basic foods, remain the same. The lunch and supper menus include more soup and rice dishes.

Monday – lunch: Minestrone with rice, Lombard style; stewed meat with potatoes

Monday – supper: Pasta in broth; boiled meat with pickled vegetables or a green

salad.

Alberto: Finally in Belmont County

Once Alberto arrived in New York, he had to take a train to Bellaire, Ohio. Like other immigrants who didn’t speak English, Albert probably faced traveling alone as a somewhat daunting task. To make sure he made it to the right place, he wrote his father’s address on the back of a small card in his passport, not once, but twice.

He also wrote the name of a local contact, Ascenzo Morlacci. Mr. Morlacci was a coal miner living in Bellaire who later became a well-known local portrait photographer. He hailed from Barisciano, Italy, the same hometown as the Marinelli family, and was a contemporary of Alberto’s father, Giuseppe Antonio.

Marinelli, Giuseppe N[umber] 366 22 -

and St Bellaire

Ohio North

Morlacci Ascenzo

Marinelli Giuseppe N[umber] 336-

22 and St Bellaire

Oho[sic] North America

Alberto: Living in Belmont County

Soon after arriving in Belmont County in 1928, Alberto joined his father in working in the local coal mines. Around this time Giuseppe Antonio also tended to a very important matter: He went to the Court of Common Pleas in St. Clairsville and obtained documents attesting to the fact that he and his three sons were naturalized citizens.

Gilda: Early years

Gilda Capitini was the oldest child of Enrico (or Enerico) Capitini and Gina Piccardi Capitini. Both Enrico and Gina came from small towns near Assisi, the capital of the province of Umbria, Italy. Enrico was born in Sant’Egidio; Gina, in Petrignano d’Assisi.

After they married, they lived in Petrignano d’Assisi in a small house with a central stone fireplace that served for both heating and cooking. Life in the early 1900s in rural Italy was challenging, at best.

Although the peninsula of Italy had finally been unified into a single nation by 1870, there was still much political turmoil, social chaos, poverty, and illiteracy in the early 1900s. Enrico and Gina’s difficult life contrasted greatly with the relative peace and prosperity of Italian emigrants already living in the United States. One of those early emigrants was Enrico’s brother, Cesare (Caesar), who had found stable work in the mines near Piney Fork years earlier. Enrico and Gina decided to join him in America.

On January 7, 1910, Enrico and Gina boarded the steamship S. S. Berlin in Naples, Italy, and embarked on their journey to America. They arrived at Ellis Island, in New York, on January 18. From there they made their way to the Ohio Valley. Gilda was born just four months after her parents’ arrival in the United States.

Enrico and Gina eventually had five children, one of whom died as a toddler: Gilda, Adolph Anthony, Lydia, Emilio, and Nevo. In this photo, Gilda (pronounced JILL -duh) is pictured with a younger brother, Adolph, and her parents. Their nicknames were written on the photo; Adolph was called “Dot” because he was so small.

Gilda: Going to school in Bellaire

Enrico and Gina moved from Piney Fork to West Bellaire, near Schick’s mine when Gilda was a young child. Enrico mined coal and kept a large vegetable garden behind their modest home on Route 2 to support the household. Gina made a home for their growing family and cared for the occasional boarder.

Coming from a country where illiteracy was high, the Capitinis made sure that their children attended school and learned to speak English. However, immigrants and their children were not always looked upon kindly, even though 15 to 25 percent of the population of Belmont County in 1920 was foreign-born, according to the federal census. Some of Gilda’s classmates taunted her and the other children of immigrants by calling them derogatory names, such as “hunky”.

Gilda persisted. She graduated from Bellaire High School in 1930, where she completed a commercial course of study. This was an extraordinary achievement, as only about 29% of U.S. students graduated from high school in 1929-1930.

Although Belmont County, along with the rest of the country, was in the midst of the Great Depression, the Capitinis found the money to make sure Gilda could buy a class ring and yearbook to mark the occasion. Gilda, too, was very proud of her accomplishment and remained close to many of her high school friends, attending both the 25th and 50th high school reunions in the years to follow.

Alberto and Gilda: Marriage and family

In the early twentieth century, immigrants in the Ohio Valley often formed close ties with those who shared their native language, foods, and customs. Gilda most likely met her future husband Alberto through this network of friends and relatives. They married in April of 1935.

Since money was scarce during those hard times of the Great Depression, Alberto and

Gilda moved in with her parents in West Bellaire at R.F.D 2, Box 91. They lived there for

more than five years before relocating to a rental home in Bellaire in the neighborhood

near the Imperial Glass Factory.

Gilda and Albert eventually had three children: Joseph was born in 1937, while the

family was living with her parents in West Bellaire. Albert Jr. (1943) and Patti (1952)

were born while the family lived in Bellaire.

Alberto and Gilda marked these important events in their lives with portraits at the

Morlacci studio. The same man who had been Alberto’s contact when he arrived in

Bellaire in 1928 had become a popular portrait photographer in Bellaire and created

these photos.

Alberto and Gilda: Mining life in the 1930s

Having moved in with her parents after marrying in April 1935, Alberto and Gilda began

a life of toil and thrift together. In addition to Gilda’s parents, the household also included her younger brothers, Adolph and Nevo. Everyone contributed to the well-being of the family.

In the 1930s, steady work was scarce and times were tough, due to the worldwide

economic turmoil known as the Great Depression. To help cover expenses, the Capitini

- Marinelli family took in boarders. Gina and daughter Gilda spent their days taking care

of their lodgers and family members. On weekends, the men in the family tended a

large vegetable garden, which helped supply the family’s food. But during the week,

they worked in the local coal mines whenever they could.

In the 1920s, coal production had increased, due to the growth of glass and steel works in

the Ohio Valley. However, even coal mining took a downturn during the Great

Depression and the 1930s. Full-time work was hard to find and miners often worked

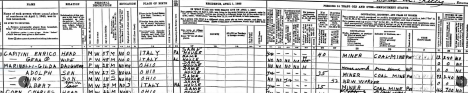

only a few days a week. Earnings fell dramatically. This detail from the 1940 census

indicates the wages that the three miners in the family had earned in 1939. These

wages were about half of what the average American coal miner was earning before the

Crash of 1929 (U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1934).

Enrico, age 57, head of the household, had worked 12 weeks in 1939 and

earned $240 ($20 a week).

Adolph, age 27, had also worked 12 weeks and earned $240 ($20 a week).

Alberto, age 29, had worked 46 weeks and earned $700 (about $15 a week).

Albert and Gilda: Mining life in the 1940s

As the Great Depression wound down in 1940, coal production began to rebound and coal mining work once again became more plentiful. The demand for coal grew even greater when the United States entered World War II, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Coal mining became increasingly more mechanized; in the larger mines, automated underground equipment was used to mine coal and bring it to the surface.

Nevertheless, coal mining work continued to be dangerous, with fires, explosions, and cave-ins. Every miner and his family lived in dread of a repeat of the 1940 Willow Mine disaster, near Neffs, in which 72 men perished; or the 1944 Powhatan Mine fire, in which 66 miners lost their lives.

Throughout the first half of the decade, Albert continued to work in company coal mines in the Ohio Valley. As seen in the photograph with his fellow miners, Albert’s daily gear included his work clothes, a hard cap with a lamp, and a dinner bucket – which Gilda prepared for him each day.

At the end of World War II, Albert also ventured into business on his own and with relatives. One such venture was the C& M Coal Company, which he co-owned with his brother-in-law, Adolph Capitini, from 1946-1949. Their small mine called the Echo Mine was located in Neffs. Unlike the large company mines, which by this time generally used heavy machinery to mine coal, this small mine relied on black powder (explosives), picks, shovels, and a cart with a mule. Alberto and his brother-in-law performed this back-breaking work during the week; on weekends, Alberto and his second son, Albert Anthony, would drive to Neffs in his black 1940 Chevy to feed the mule.

Albert and Gilda: A “Detour” during World War II

The United States entered World War II in December 1941, following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The country immediately began to ramp up production of military equipment, and jobs in mining and other industries once again increased

To make sure there were enough resources available to fight the war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established a rationing program. Rubber tires and gasoline were among the first items to be rationed to civilians, followed by food in May 1942. The Office of Price Administration established local rationing boards across the country and issued Ration Books. At first, only sugar and then coffee were rationed; by the following year, rationing was applied to meats, oil, butter, canned goods, and some other foods. Civilians had to turn in stamps from the Ration Books in order to purchase those scarce

supplies.

During the war years, under the leadership of John L. Lewis, the United Mine Workers

of America trade union became even more powerful. Union strikes and walkouts were

countered by federal government seizures of coal mines for several years.

During this time, the Marinelli family, like other Americans, sacrificed for the war effort

and pondered the best way to provide for their growing family. For a short time, in 1944,

they moved from Bellaire to Detroit, where Alberto’s brother Raffaele lived. But after just

a few months, they returned to Belmont County, where both Alberto and Gilda had

siblings, nieces, and nephews.

Albert and Gilda: Mining life in the 1950s

Through the 1950s, mining continued to be the organizing principle for the Marinelli

family. Albert had studied to become a mechanic and was working at the Powhatan No.

1 mine (North American Coal Company), where he repaired large underground mining and loading equipment.\

Each week Albert worked a different shift: day shift (from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m.), afternoon

(from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m.), and midnight, or “hoot owl” (from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m.). Travel

time between his home in Bellaire and the mine in Powhatan made the days even

longer; added to that was the time spent showering and changing at the mine at the end

of a shift. On top of these already long days, sometimes Albert would work a double

shift, to earn extra money or to cover for someone who was out sick.

Gilda’s schedule also revolved around the three shifts, as she packed dinner buckets

and prepared meals to accommodate her husband’s timetable. She always served

supper at 5:00 p.m. on the dot -- just minutes after Albert arrived home from working

day shift, or shortly after he awakened from sleep when working the midnight shift.

The regular rhythm of shift work was broken only when there were mine walkouts and

strikes. The UMWA continued to be a powerful voice for miners. In 1946, a historic

agreement had been reached by the UMWA, the federal government, and coal

operators to establish and maintain a pension and healthcare plan for miners. Then, in

1951, an agreement was reached which provided for a boost of 20 cents an hour in

miner wages. Similar increases were earned every year or two throughout the 1950s.

Albert and Gilda: Mining life in the 1960s and beyond

The 1960s were generally a time of peace and prosperity for the Marinelli family. After

saving for 25 years, Albert and Gilda were able to buy their own home. With the help of

many friends and relatives, they built and moved into a new brick house on Lincoln Avenue in Shadyside.

The coal mining life in the 1960s was much like it had been in the previous decade.

Weekdays were dedicated to work: Albert, repairing machinery at Powhatan No. 1 coal mine; Gilda, managing the household and children. Saturday mornings were spent shopping in the bustling downtown of Bellaire, at the A&P, Murphy’s, Isaly’s, and Italian specialty shops. Sunday afternoons were dedicated to visiting with relatives and friends or attending the meetings of the Italian-American Club.

Summers brought new diversions to the routine: a picnic at Tappan Lake (complete with homemade Italian pasta), an afternoon at Oglebay Park or Wheeling Park, a morning spent blackberry-picking in the hills, a long drive in the winding roads of Belmont County.

During the 1960s the two older children – Joseph and Albert Anthony—got married and

the grandchildren started to arrive, five in all by the end of the decade. A time for looking back,with pride.

Then came the 1970s and sorrow; in 1973 Albert became seriously ill, the result of his many years working underground in the coal mines. He died in 1975. Gilda continued to live at the house in Shadyside and died in 2004.

This is one of the last photos taken of Albert and Gilda before Albert became ill. In a light moment, Gilda -- who had never worn pants or shorts in her life -- donned daughter Patti’s “college clothes.” Albert, still strong at age 62, lifted her up like a new bride.

Author’s Note

This family history is compiled from my recollections and those of my relatives, along with information found in our various historic documents and artifacts. I also consulted numerous sources in print and online, including the federal census from 1920, 1930, 1940, and 1950 and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

I am indebted to my lifelong friend Carma Kovalo for reviewing an earlier draft of this narrative and providing many helpful suggestions.

I hope this narrative provides a glimpse of life in Belmont County for an immigrant coal-mining family in the first half of the twentieth century. Perhaps others will find similarities with their own family histories and be inspired to dig deeper, as I did.

Looking back on my family history, I am amazed at how much I didn’t know about my parents’ lives, their challenges, and their joys. I have included in this narrative those stories and events that are closely related to the documents and other artifacts of this collection. And I cherish in my heart many more examples of love and sacrifice that I have uncovered in my research but have not detailed here.

I dedicate this work and this collection to the memory of my parents, Albert and Gilda

Marinelli.

.png)

Comments